This article was inspired by a presentation by Dave Dunbar (Freestyle Farms) at a Hapi Research Symposium in Wellington. Parts contain quotes from an article in Growler Magazine, graphics from Dave Dunbar, Stan Heironymous and Barth Haas.

Definition of Terroir: A French word meaning the complete natural environment in which a particular agricultural product is produced, including factors such as the soil, topography, and climate.

Name a hop, and craft beer drinkers will tell you exactly how it tastes. The resinous pine of Simcoe. The juicy citrus of El Dorado. The earthy spice of Saaz.

One way craft beer fans have learned about hop flavors is through SMaSH recipes, so called because they’re brewed with a “Single Malt and Single Hop.” These recipes challenge a brewer to highlight the nuances that distinguish each ingredient, and they serve as fine educational tools—the next time a drinker sees a beer called a “Citra Pale Ale” for example they will have an idea of what that means.

But ask those who grow hops and brew with them, and they’ll say the idea that a hop variety has a single set of personality traits is misguided. They know that no two Citras are the same. From state to state, year to year, or even row to row on the same farm, the “same” hops can deliver markedly different flavors to the finished beer.

Even though beer can be made at any time of year, it is still, like wine, an agricultural product. And like winemakers, brewers have wondered exactly how much of this flavor variation has to do with exactly where the hops are grown, and how they express that sense of place—that mysterious quality the wine world knows as terroir.

Ruhstaller of Dixon, California developed a series of beers with that question in mind. It features four beers, identical in every way (batch size, malt bill, yeast, process) except for the place the hops were grown.

Three of the batches used Cascade hops from individual farms in areas of northern California with distinct elevations, soil, and microclimates. The fourth used what Ruhstaller calls ‘Orphan’ hops—what most of the craft beer industry uses—Cascades purchased through a broker and grown in an undisclosed location in the Pacific Northwest.

“The point is not to say which one is better or worse,” says J.E. Paino, owner of Ruhstaller. “This is: do you taste a difference? And if you taste a difference, then it matters. And it opens up another conversation about beer, which is ingredients.”

The feedback indicated that it does indeed matter where hops are grown. “Everyone, 100 percent, say there is a difference. Most folks, 90 percent, discuss which one they like better. The [remaining 10 percent] talk about characteristics,” J.E. says conclusively. “They typically say [the beer with hops from] Dixon is smooth and fruity, Sloughhouse is aromatic and sweet, Lake County is piney, and Orphan tastes like ‘fill in the blanks’ IPA.”

But when the conversation turns to how much of those differences are due to terroir, the answer is less black and white. The effects of terroir are likely overshadowed by the effects of other, more prominent factors.

“The largest impact on hop characteristics is how well they’re grown, harvested, and packaged,” explains Eric Sannerud, co-founder of Mighty Axe Hops. “By far, that matters the most. Something like 80 to 90 percent of hop quality is harvesting and growing.”

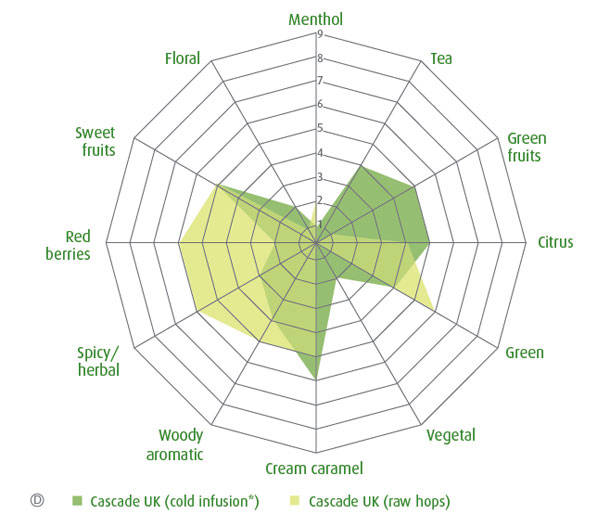

“There are definite differences from, say, Cascade grown in the Yakima Valley versus Cascade grown in Germany,” comments Dave Berg of August Schell Brewing Company. “But even within hops grown in the same region, there is variability from year to year and even variability in the same year.”

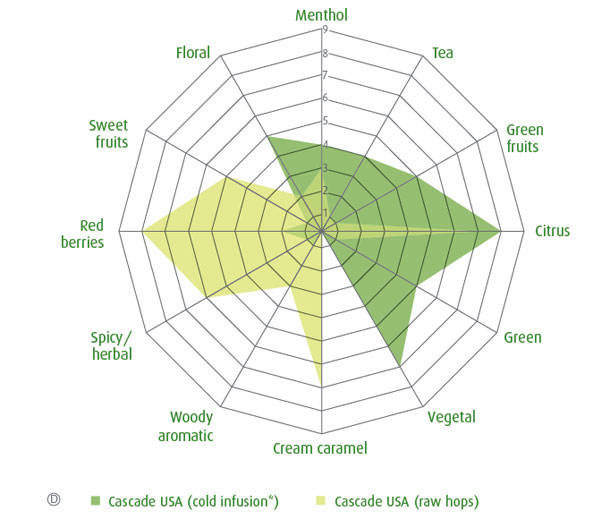

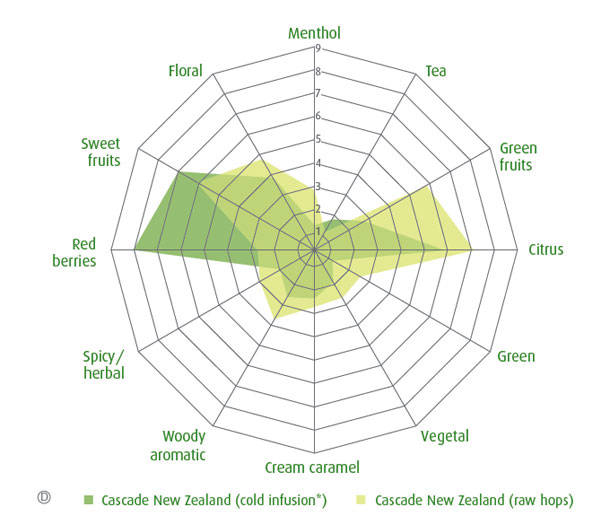

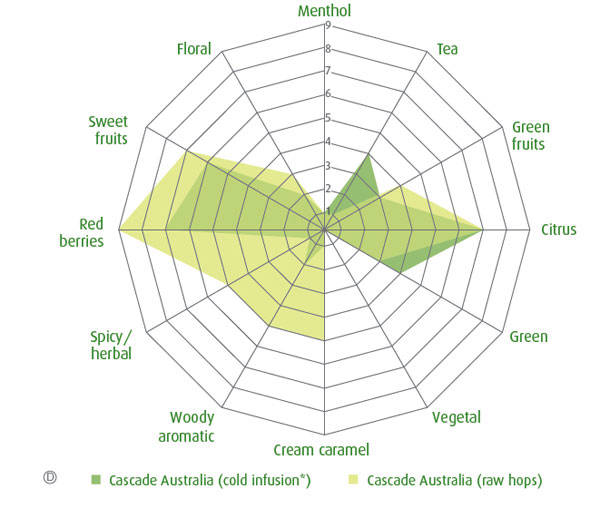

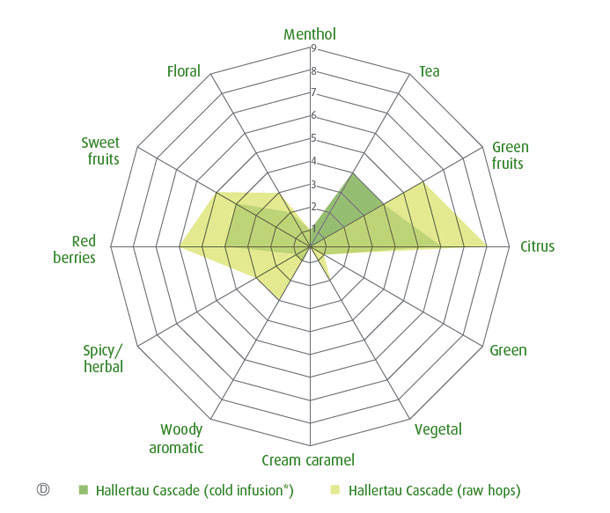

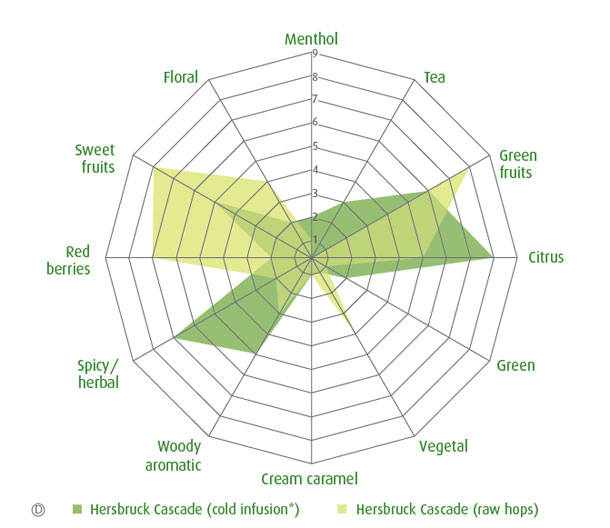

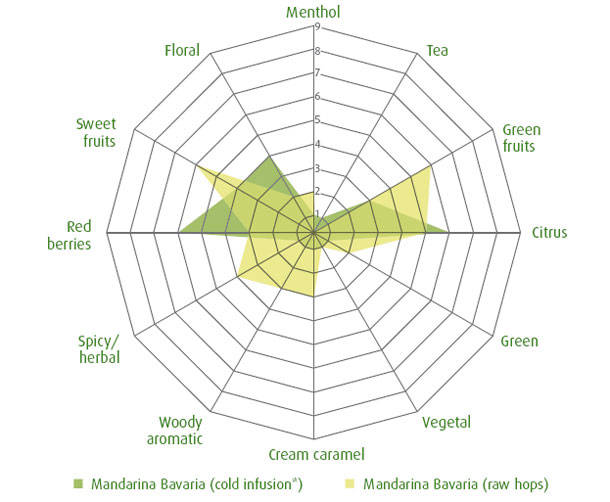

Mandarina Bavaria is included in the spider graphs above. It is one of the German hop varieties released in 2012, is a daughter of Cascade and is already very popular with American breweries (it is prominent in Firestone Walker’s Easy Jack included in our recipe page). Like its mother, it is rich in geraniol.

Wild About Hops offers another daughter of Cascade for sale, Tangerine Dream, which was bred by Monhopoly in NZ and also has a German male in it's lineage.

Variability is a problem for breweries who need a huge supply of a certain flavor of hops for their popular flagship beers. “We do pay close attention to hop deviation because it is necessary to create consistency in our brands,” Hoops says. “We define the flavor and aroma profiles for the hops we use and search for that profile each year. If we cannot find the profile we want, we address that by adjusting the blend in the recipe to achieve our profile.”

Smith notes that at Surly, they try to pick exact hop lots that inherently exhibit the brand profile, but that “if we have multiple lots of a single hop variety, we will try to blend the hops consistently. We can adjust the individual hop amounts in the blend to maintain a consistent ‘true-to-brand’ product”.

If this seems like a missed opportunity to showcase the unique qualities of the hops, Paino suggests the brewer is not at fault—they are brewing to consumer preferences.

“Our challenge with this is that the consumer is expecting consistency, and they think that’s perfection. That if the beer doesn’t taste the same all the time, then it’s bad. If Pliny the Elder tastes different, [Russian River brewer] Vinnie [Cilurzo] has lost his touch. So how does he make sure it tastes the same to very smart beer drinkers? He’s making sure he blends the hops from all different farms.”

He argues that using consistency as a measure of quality in craft beer is counterintuitive to an industry that celebrates authenticity: “We have the same expectations of Sierra Nevada Pale Ale as we do of a Big Mac. But how do you [achieve] that with ingredients that are naturally imperfect? You gotta dumb it down. And that’s what we’ve agreed to as consumers.”

For their part, hop growers see opportunity in natural variance. They envision a craft brewing scene that could highlight it as local flavor instead of hide it as an imperfection.

“We’re competing in a huge industry dominated by the Pacific Northwest,” explains Brian Deal of the Minnesota Hop Growers Association. “We’re trying to look for what makes up the local edge and how to prove it. So when I take hops from my farm, I can say, here’s what the terroir has done with the Cascade hops I grow. This [character] is what you’re gonna get.”

Growers also know that this opportunity can only be realized if the narrative with beer drinkers changes, and they think the time is right for it to change.

“Ten years ago, I don’t think people would be interested in the difference between hop varietals in a beer,” says Sannerud. “Now, there’s absolutely no reason that [some consumers] don’t want to know [not only] where hops are grown, but also how that influences the flavor of beers that we’re enjoying.”

Growers are confident in the benefits of recognizing hop terroir but know there needs to be evidence to show that the influence of terroir is real. With a motto of “Taste the Terroir,” Mighty Axe Hops is taking on the task of finding evidence that where a hop is grown has a measurable impact on hop flavor and aroma.

“We received a [Minnesota] Department of Agriculture grant for money to develop a science-based program of sensory analysis, aimed at identifying the unique aroma of hops grown in Minnesota versus out West,” says Sannerud. Their experiment will control for two confounding variables that account for the majority of flavor and aroma variation within a single hop variety—the maturity of the cone, and the temperature at which it’s dried.

“We’re really trying to build a standard of something that is publishable data,” he says. “Our hypothesis is that there is a difference. What we’re doing with a science-based approach is really developing a new set of knowledge for the craft beer industry.”

Empirical evidence of hop terroir could change the way the industry treats inconsistency in hop profiles. But for breweries to be able to sell hop terroir as authenticity, consumers need to value natural variation instead of vilifying it. Consumer perceptions need to change, and for consumer perceptions to change, there needs to be proof that place matters.

And if consumers begin to value the influence of terroir, it gives local hop farms the ability to offer more benefits than just its proximity. “Local has to be more than, yeah, well, they’re down the street,” explains Paino. “It has to mean better, or different. When you celebrate terroir, you celebrate the difference.”

Thanks to: Stan Hieronymus, Bart Haas, Dave Dunbar from Freestyle Farms - Parts of this article contains quotes from an article in Growler Magazine